As we continue to learn more about the implications of gastrointestinal inflammation on the immune response, digestive health and longer-term health risks, the need to expand our natural medicine toolkit to support a reduction of inflammation, or inflammation causing pathologies, is critical.

In 1920 during a cholera outbreak1, microbiologist, Henri Boulard, first documented the benefit of Saccharomyces boulardii (S. boulardii) in Indonesia after observing the use of a tea made of lychee skins and mangosteen fruits for the prevention of diarrhoea.2 One hundred years later, S. boulardii, continues to be a mainstay in the prevention and treatment of diarrhoea.1

Commonly associated with gut inflammation, diarrhoea continues to be one of the leading causes of morbidity and hospitalisation worldwide alongside meaningful economic burden.2 This continued prevalence emphasises the demand for alternative therapies from the standard protocol of hydration and electrolyte therapy, both ineffective at reducing stool volume, frequency and duration of diarrhoea.2

In this article, we put the spotlight on S. boulardii, a probiotic lauded for its benefits in reducing gut inflammation, and for the treatment and prevention of diarrhoea-associated conditions including traveller’s diarrhoea.

What is Saccharomyces boulardii?

Categorised as a probiotic within the World Health Organisation’s definition of a ‘live microorganism that confers a health benefit on the host’,1 S. boulardii differs from bacteria probiotics as a eukaryote probiotic yeast.2 While similar to Saccharomyces cerevisiae or baker’s yeast,3 S. boulardii has “different taxonomic, physiological, metabolic and genetic” properties.2

S. boulardii has an optimum growth temperature of 37 degrees celsius,1 consistent with human body temperature.2 The yeast can maintain 65% viability up to 52 degrees celsius3 allowing for a shelf-stable product. While other treatments may be challenged by the gastrointestinal environment, S. boulardii is resistant to low and high pH and bile acids, allowing it to survive the gastrointestinal tract1 for up to 3 hours.3 To support supplementation, encapsulation in sodium alginate or gelatin allows S. boulardii to remain viable in the presence of bile salts for longer.3

With a half-life of six hours, consistent administration of S. boulardii results in steady-state concentration from three days of administration, taking a further 2-5 days to clear the body from the point of discontinuation.1

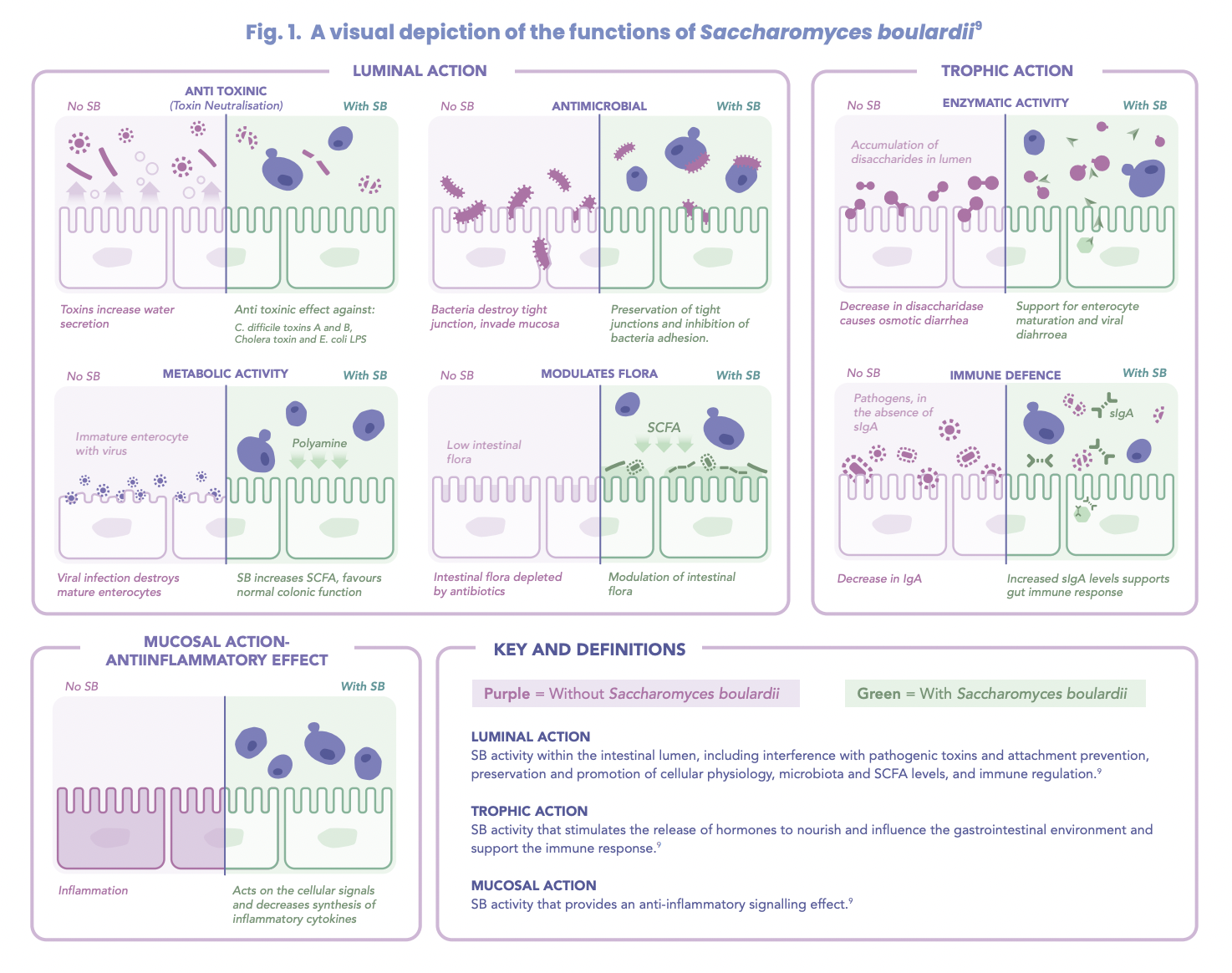

Transient and unable to effectively colonise the intestine long term due to its inability to adhere to the epithelium, S. boulardii can influence the microbial profile of the individual to an extent, based on the pre-existing gastrointestinal microbial composition.3 This selective action of S. boulardii on the microbiota differentiates it from the actions of other probiotics.9

An impressive safety profile

S. boulardii has an excellent safety profile with minimal adverse reactions.3

The presence of translocated fungus or yeasts within the blood from the gut, is known as fungemia.4 A retrospective study identified the use of S. boulardii as a risk factor for the development of fungemia and recommends extreme caution when administering S. boulardii to the elderly patient more susceptible to translocation due to altered gut permeability.4 Furthermore, S. boulardii is contraindicated in intensive care, those hospitalised with a central venous catheter, immunocompromised or critically ill patients.4

A means to reduce gastrointestinal inflammation

Intestinal permeability controls the transport of substances across the gastrointestinal epithelium and into circulation.5 Altered intestinal permeability results in increased inflammation, pathogen translocation, and potential disease progression, including Crohn’s disease.5 Translocation of lipopolysaccharides promotes inflammation through the release of IL-6 and TNF-a, a process counteracted by S. boulardii through the enhancement of IL-10 levels, a known anti-inflammatory.6

S. boulardii limits inflammation by production of the protein phosphatase 63 kDa, capable of reducing the toxicity of lipopolysaccharides, and reducing inflammation.6 Within the cell, S. boulardii functions to inhibit the production of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-8 by inhibiting the NF-kB and MAPK signalling pathways.6 Further studies have demonstrated that a preexposure to S. boulardii reduces inflammation by stimulating the production of immunoglobulins and cytokines, to support the immune response to future infection.6

The best use of S. boulardii

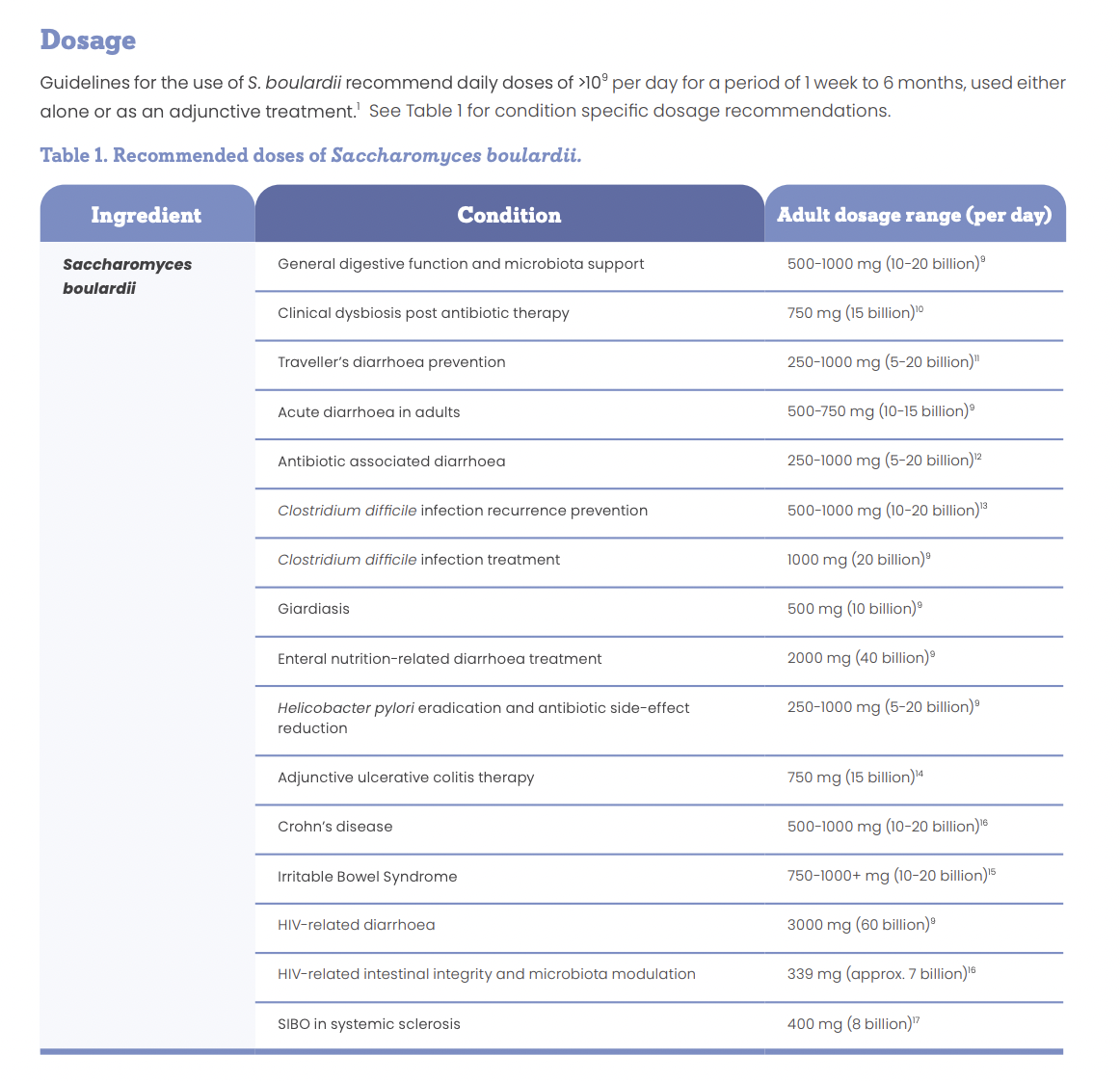

Due to its favourable role in gastrointestinal health, the therapeutic benefits of S. boulardii focus on the reduction of diarrhoea and inflammation and microbiome restoration.

Diarrhoea treatment

Well-regarded for its role in reducing diarrhoea, S. boulardii influences short chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, involved in water and electrolyte absorption.7 One of the most researched functions of S. boulardii is its ability to reduce hospitalisation and diarrhoea duration7 with the mean reduced by 24 hours.2

Acute paediatric diarrhoea

Of 24 randomised control trials looking at the efficacy of S. boulardii to treat paediatric diarrhoea, 83% also found S. boulardii beneficial in reducing acute diarrhoea by up to one day, with no adverse events identified.1 Typically, the treatment period for these trials was seven days with doses ranging from 1 x 1010 CFU/day to 500 mg/day.1 A meta-analysis found a reduction in the stool frequency from day 2 of treatment with S. boulardii2 suggesting benefits to recovery also.

Antibiotics and S. boulardii – the perfect match

Often prescribed alongside the use of antibiotics for the reduction and prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD), studies looking at AAD in the treatment of Clostridium difficile demonstrated both a preventative and curative effect of S. boulardii.7 Studies involving the use of antibiotics known to reduce SCFA levels in conjunction with S. boulardii have demonstrated S. boulardii’s ability to maintain SCFA levels during antibiotic therapy.7 Early administration of S. boulardii at the commencement of antibiotic therapy has been shown to offer greatest benefit.7

Unlike most probiotics, S. boulardii is resistant to antibiotics2 and does not contribute to antibiotic resistance due to its fungal nature2 supporting its concomitant use with antibiotic therapy.

Saccharomyces boulardii for the treatment of traveller’s diarrhoea (TD)

Affecting more than 20 million tourists annually, TD impacts 38-79% of travellers travelling to developing countries.8 Predominantly associated with pathogenic bacteria including Escherichia coli, Campylobacter jejuni, Shigella, Salmonella, and Yersinia enterocolitica,7 the average TD bout lasts for 1-4 days, with 3% of sufferers requiring hospitalisation.8 Long term implications of TD include symptoms extending beyond 90 days post-infection and the development of post-infectious complications including irritable bowel syndrome.8

An Australian study demonstrated a 10% decline in TD with the administration of 1 g/day to study participants when administered five days prior to travelling and continued throughout the travel period2 (approximately 3 weeks in duration).1

Helicobacter pylori infection

Involving 1-2 antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection, studies have identified that the additional treatment of S. boulardii reduced the incidence of antibiotic associated diarrhoea in 93% of the treatment groups.1

With research into the therapeutic benefits of yeasts centring around the S. boulardii strain, further investigation into other yeasts may be beneficial. Strong evidence supports the use of S. boulardii for the prevention and treatment of acute diarrhoea, whether it be from travel, antibiotic use or other aetiology. S. boulardii also supports the reduction of inflammation produced as a result of gastrointestinal injury or infection, making S. boulardii an essential supplement for all first aid kits.

Download a Free PDF Version of this article

References

1. Mcfarland, L. V. (2017). The Microbiota in Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology Common Organisms and Probiotics: Saccharomyces boulardii. In The Microbiota in Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804024-9/00018-5

2. Dinleyici, E. C., Eren, M., Ozen, M., Yargic, Z. A., & Vandenplas, Y. (2012). Effectiveness and safety of Saccharomyces boulardii for acute infectious diarrhea. In Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy (Vol.12, Issue 4, pp. 395–410). https://doi.org/10.1517/14712598.2012.664129

3. Pais, P., Almeida, V., Yılmaz, M., & Teixeira, M. C. (2020). Saccharomyces boulardii: What makes it tick as successful probiotic? In Journal of Fungi (Vol. 6, Issue 2, pp. 1–15). MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof6020078

4. Poncelet, A., Ruelle, L., Konopnicki, D., Miendje Deyi, V. Y., & Dauby, N. (2021). Saccharomyces cerevisiae fungemia: Risk factors, outcome and links with S. boulardii-containing probiotic administration. Infectious Diseases Now, 51(3), 293–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idnow.2020.12.003

5. Odenwald, M. A., & Turner, J. R. (2013). Intestinal Permeability Defects: Is It Time to Treat? Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 11(9), 1075–1083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.001

6. Stier, H., & Bischoff, S. C. (2016). Influence of saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 on the gut-associated immune system. In Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology (Vol. 9, pp. 269–279). Dove Medical Press Ltd. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEG.S111003

7. Czerucka, D., & Rampal, P. (2019). Diversity of Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 mechanisms of action against intestinal infections. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 25(18), 2188–2203. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i18.2188

8. McFarland, L. v., & Goh, S. (2019). Are probiotics and prebiotics effective in the prevention of travellers’ diarrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 27, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.09.007

9. McFarland LV. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Saccharomyces boulardii in adult patients. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16(18):2202-2222.

10. Abbas Z, Yakoob J, Jafri W, et al. Cytokine and clinical response to Saccharomyces boulardii therapy in diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;26(6):630-639.

11. McFarland LV, Goh S. Are probiotics and prebiotics effective in the prevention of travellers’ diarrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis 2019;27:11-19.

12. Szajewska H, Kolodziej M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Saccharomyces boulardii in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42(7):793-801.

13. Carstensen JW, Chehri M, Schønning K, et al. Use of prophylactic Saccharomyces boulardii to prevent Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized patients: A controlled prospective intervention study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2018;37(8):1431-1439.

14. Dinleyici EC, Kara A, Ozen M, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 in different clinical conditions. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2014;14(11):1593-1609

15. Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K., Ruszkowski, J., Fic, M., Folwarski, M., & Makarewicz, W. (2020). Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745: A Non-bacterial Microorganism Used as Probiotic Agent in Supporting Treatment of Selected Diseases. In Current Microbiology (Vol. 77, Issue 9, pp. 1987–1996). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-020-02053-9

16. Villar-Garcia J, Hernandez JJ, Guerri-Fernandez R, et al. Effect of probiotics (Saccharomyces boulardii) on microbial translocation and inflammation in HIV-treated patients: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;68(3):256-263.

17. García-Collinot G, Madrigal-Santillán EO, Martínez-Bencomo MA, et al. Effectiveness of Saccharomyces boulardii and metronidazole for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in systemic sclerosis. Dig Dis Sci 2020;65(4):1134-1143.